This post was realized in collaboration with a fellow student. We worked on this a couple of weeks ago, when Greece was negotiating an extension of the bailout with its international partners. We did this out of curiosity and to explore whether this could make an empirical motivation for a paper on public debt instruments. That is why this post is somewhat more elaborated than the previous ones (and a less “disconnected”).

———————————————————————————————————————————–

The newly elected Greek government proposed to swap the European rescue bonds with GDP-linked ones.[1] The main argument in favor of this type of securities is that it forces debtor countries to align their objectives to those of the borrowers. However, the benefits of GDP-linked bonds can be seriously undermined by measurement issues. We show that revisions of Greek GDP measures have been changing wildly in recent years. This casts doubts on the accuracy of GDP data and suggests that the choice of a more reliable indicator of economic performance could overcome some of the problems related to this kind of securities.

GDP-linked Bonds

GDP-linked bonds are not new in the economic debate and have been discussed at length in the literature. The underlying idea is to compare the performance of a country’s economy, measured in terms of nominal and real GDP, against some reference values set ex-ante in the contract. These instruments offer major benefits for countries in debt distress mainly because they favor a countercyclical fiscal policy (Borensztein and Mauro, 2004) and they should in principle let governments and borrowers share a common objective. However, they are not free of concerns. In particular, GDP mis-measurement and moral hazard could weaken their benefits.

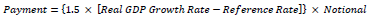

In March 2012 Greece signed a debt-restructuring deal in a context of a Private Sector Involvement (PSI) in which part of the existing debt was swapped to a new contract and linked to GDP performances. Considering this as a relevant precedent, we take into consideration the payment scheme adopted at that time as a reference. Following Zettelmeyer, Trebesch and Gulati (2013), the annual payments are computed on October 15 for the preceding year. Payments are made only if (i) nominal GDP in the preceding year exceeds some reference amount and (ii) real GDP growth exceeds some reference rate and is non-negative. If these conditions are met, the annual payment is computed as follows:

The reference values for both nominal GDP and real growth rate are time varying. They are set ex-ante in the contract and based on forecasts. The actual yearly measures are those published by EUROSTAT, whose statistics come from National Statistical Institutes.[2]

GDP measures and their revision

All the variables involved in the computation thus rely either on data directly provided by the borrowing country’s National Statistical Institute, like the previous year’s real GDP growth rate and nominal GDP, or forecasted using those data. Are these measures reliable? Could they be subject to misreporting? We try to answer these questions by using OECD real-time data vintages – whose sources are precisely the National Statistical Institutes – and check whether subsequent revisions cast doubts on the reliability of the data.

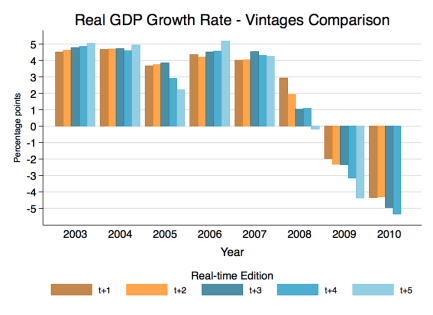

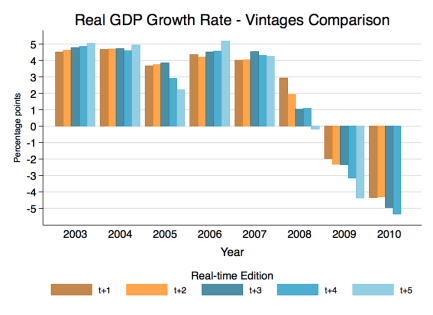

Figure 1 shows the revisions of real GDP growth in the October of the year of the first release and the 4 subsequent years. Similarly, Figure 2 plots the Greek real GDP growth rates over the last decade averaged over the first five available vintages together with their standard deviation. Two things emerge from these figures. First, revisions can be large (as much as 3.12 percentage points in our sample) and the value does not seem to converge necessarily to a steady value in the short run. Second, revisions seem to be bigger during the crisis. A similar pattern emerges when analyzing GDP vintages of the UK, as if statistical offices have more difficulties to calculate GDP in a recession.[3] This might be a source of extra-concern, since it suggests that GDP estimates are less accurate exactly in the moments in which GDP-linked bonds are of more importance.

Figure 1: Each column represents the growth rate of the considered year t, according to the first five real-time data releases, which take place starting from t+1. We use October’s vintages from years between 2004 and 2012. In years 2013 and 2014 October’s vintages are not available, so the July and December’s vintages have been used, respectively.

Source: OECD Stats – stats.oecd.org.

Figure 2. The orange line represents the real GDP growth rate averaged across vintages, while columns depict the cross-vintages standard deviations. Both statistics are computed using the first five data releases. We use October’s vintages from years between 2004 and 2012. In years 2013 and 2014 October’s vintages are not available, so the July and December’s vintages have been used, instead.

Source: OECD Stats – stats.oecd.org.

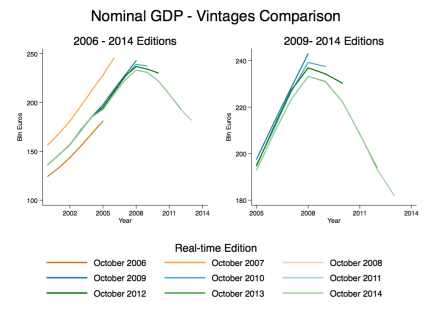

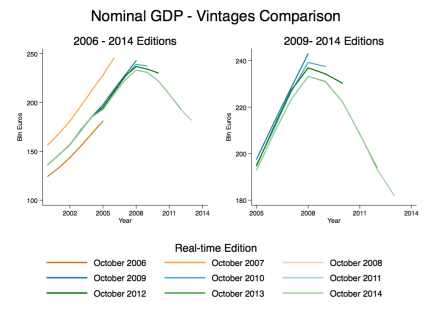

The swings in real GDP estimates are only in part due to revisions of the price indices. Figure 3 reports the nominal GDP estimates released between October 2006 and October 2014 and shows that the nominal series is not immune to changes across years. The differences between October 2006 and 2007 and the other real time editions is striking, but as the second panel shows more recent data are far from being consistent.

Figure 3: The left panel plots all the series released between October 2006 and October 2014. The right panel focuses on the difference of the 2009-2014 series.

Source: OECD Stats – stats.oecd.org.

Discussion

Keeping the payout scheme described in the first section in mind, the figures above show that large changes in the revision seriously weaken the argument in favor of GDP-linked bonds because they would significantly alter yearly payments and cast doubts on the accuracy of GDP estimates. In 2008, for instance, the GDP-linked bonds would have turned out to be pro-cyclical since the growth estimate in October 2009 was around 3%. Moreover, as feared by Borensztein and Mauro (2004), investors could feel cheated by such changes in the revision.

Borensztein and Mauro (2004) suggest that it is unlikely that governments would consistently under-report their GDP figures, since it is easier to be re-elected when the economy is strong and growing. However, this automatic control mechanism might not be fully working when payments are allocated with a lag compared to when the first growth estimate is released.[4] In this case, it might be possible for politicians to get the political benefits of announcing a high growth rate and then revise the figures downwards before the payments. For example, the first release of national account data for each year, according to OECD vintages, is usually released in March of the following year. The Government can therefore benefit from the March announcement and then revise downwards before the October payments.

There might be three ways around this issue. First, as proposed by Panizza (2015) repayments could be smoothed over long periods. This approach has the downside of partially weakening the counter-cyclical benefits of GDP-linked bonds. Second, one might take the first published GDP figures as the ones used for repayments. However, such figures are usually quite unreliable since they are published in the first quarter of the successive year, when data are still preliminary. Third, the bonds could be linked to the maximum of the GDP figures published from the first quarter to the moment of the repayment. This way, the incentives of strategic reporting would be reduced.

Conclusions

GDP-indexed bonds have appealing properties and might represent a viable way for reducing Greek debt without haircuts. However, the reliability of the data and moral hazard related issues might be of some concern for investors. It is therefore important to come up with mechanisms that reduce the incentives of strategic reporting and with rules to deal with data revision and mis-measurement. A possible solution is to index the bonds to variables out of a country’s control as proposed by, among the others, Krugman (1988) or that can be measured by third-parties (as it is the case of, for example, the debt-to-exports ratio). In any case, reference values should be forecasted and discussed by all the parties involved or outsourced to an independent institution.

References

Borensztein, Eduardo and Mauro, Paolo (2004), “The Case for GDP-Indexed Bonds,” Economic Policy, 19(38), pp. 165-216.

Gulati, Mitu, Trebesch, Christoph and Zettelmeyer, Jeromin (2013), “The Greek debt restructuring: an autopsy,” Economic Policy, 28(75), pp. 513-563.

Krugman, Paul (1988), “Financing vs. Forgiving a Debt Overhang,” Journal of Development Economics, 29, pp. 253-268.

Panizza, Ugo (2015), “Debt Sustainability in Low Income Countries: The Grants versus Loans Debate in a World without Crystal Balls,” FERDI Working Paper No. 120, February.

Footnotes

[1] Financial Times, February 2, 2015. Available at: http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/7af4252c-ab03-11e4-91d2-00144feab7de.html#axzz3Qmwhjogc.

[2] The Metadata Explanatory text explains that the data sources for national accounts are National Statistical Institutes. The whole disclosure is available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/EN/nama_esms.htm.

[3] See http://www.measuringworth.com/uk-gdp-volatility.php for an analysis of UK GDP revisions.

[4] This is likely to be the case here, since it takes some time before GDP estimates are finalized.